Step by step – the longest march can be won, and by union, what we will, can be accomplished still

from the forward of Step by Step, an accounting of the Fayette County Project edited by Douglas Dowd and Mary Nichols

During the fall of 2019, Mary Nichols and Morry Cater went back to the South – each had worked there during the civil rights movement – to better understand what happened then and since.

As a junior at Cornell University, Mary traveled with fellow students to Fayette County in the summer of 1964 to register voters. “Step by Step” is the story of that project, edited by Mary and her professor Douglas Dowd.

As a junior at Harvard College, Morry traveled to Anniston Alabama, where the Freedom Riders bus was burned, to work as a journalist for the Anniston Star. Her reporting covered the after effects of the Freedom Rides, 1965 Voting Rights Act, and the deepening economic and educational divide.

Together, they traveled to Jackson, Greenwood, and Baptist Town, Mississippi, Little Rock, Arkansas, Memphis, Tennessee, Oxford, Mississippi, Birmingham and Montgomery Alabama. These are observations from their travels.

Jackson Mississippi

Driving into town late on a Saturday, the sun well down, we were struck by the enormity of highway infrastructure, seemingly disproportionate to the population. Billions invested in huge concrete ribbons of arteries, drawing people out of town central and feeding the burgeoning segregated suburbs.

Downtown roads were pockmarked, as if blasted by a volley of tiny bombs. Our car jumped and jostled as we made our way through abandoned buildings and dilapidated neighborhoods.

Granted we arrived on a holiday weekend, but Jackson was dead. We wandered out after dinner to find the highly recommended and well advertised jazz club Underground 119. It was shuttered and dark.

Our hotel bar, on the other hand, was packed. African American members of a wedding held earlier that evening still celebrated. A few tables of young white patrons dotted the room. None integrated. The staff – all African Americans – was warm, professional and very attentive. The hotel handbook advertised only all white businesses.

Sunday morning. We walked through the heart of the capital, by the antebellum city hall, and a massive, impressive and well funded government complex to the Mount Helm Baptist Church – the oldest African American church in Jackson, sitting just on its edge. The Mt. Helm neighborhood is a patchwork of well-kept sometimes new homes, empty lots and abandoned buildings. There are no businesses, much less green groceries in the immediate vicinity. The church building is old but lovingly patched and painted. As we entered, congregants stepped up to greet us.

The sermon – by a distinguished doctor and Reverend – was about diabetes, and the critical role of choice each congregant had to be healthy. There was no mention of the food deserts or economic constraints that make eating healthy organic foods more difficult if not impossible for members of this community. Instead it was a sermon full of gratitude, extolling individual accountability.

As we were leaving, several members approached, thanking us for attending, and curious about what brought us to church that day. They were clearly well educated and members of the middle class, though unclear whether they lived nearby in what did not appear to be a middle class neighborhood. We discussed what happened in the sixties, and where things stood now. And while they acknowledged that injustice continues, and the challenges to civil rights are deep and complex, they expressed heartfelt thanks to us for our commitment and contributions. Southern hospitality or sincere, or a mix of both - regardless, it was humbling.

We walked from church, down the historic Farish Street – once a robust center of blues music and southern cooking, now mostly abandoned. We followed the historic markers along a deserted string of storefronts, looking for a place to eat.

Located between two abandoned buildings sits a lively restaurant – the Iron Horse Grill – which is clearly the post church lunch spot for Jackson’s African American community – where the fried chicken is mouth watering, and the jazz saxophonist makes your bones dance.

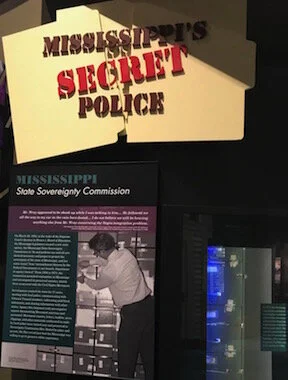

Our next stop was the Mississippi’s Civil Rights Museum, which sits in a bifurcated building shared with the Museum of Mississippi History. We did not have time for the latter, but wondered about the division. As it turns out – the latter was a well supported, funded civic endeavor, while the former took more than two decades to get approved and funded.

This is a state that didn’t pass the 13th amendment – ending slavery – until 2013. And it is the only state that continues to have the confederate flag as part of its flag. It also ranks at the bottom of the nation when it comes to education and highest when it comes to poverty.

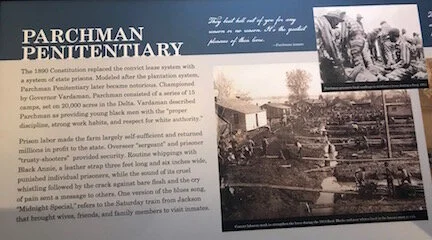

The museum exhibit halls are chockablock with stories, artifacts and data that expose in bold relief a history of oppression and torture. From 1619 and slave ships on which one in seven died during the Middle Passage, to the founding fathers betrayal in a deal to keep the South happy and codified the subhuman status of African American slaves, from the law against international slave importation to the power of king cotton and the economic drivers of a booming domestic slave trade, from the Civil War to reconstruction and the rise of the black middle class and political representation, from the abrupt withdrawal of federal troops from the South (as part of a political deal to insure the election of Rutherford Hayes) to the twisted terrifying decades that followed: Jim Crow laws, convict leasing, the rise of KKK, racial terrorism and the mass migration of refugees north, early federal government’s at best ambivalent at worst complicit role in preserving and protecting white supremacy, Brown v Board of Education and the birth of White Citizens Councils, state forged legal, political and economic barriers to the rise of the civil rights movement, freedom rides, marches, sit ins, wade ins, boycotts, culminating in critical civil rights federal laws and Supreme Court rulings.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964, passed in the wake of JFK’s assassination after a 54 day filibuster (it was the first time the Senate cut off a filibuster for a civil rights bill thanks to LBJ) outlawed discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion sex or national origin. But its enforcement powers were weak. So discrimination persisted in the deep South and the battle to resolve each injustice, one by one, in the courts began.

As a young journalist, Morry interviewed Harry McPherson, former top aide to LBJ, who was involved in the battle to integrate hospitals in Southern states, which refused, even after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 required it. Once Medicare was passed, however, and the specter of losing federal dollars loomed large, hospitals integrated overnight.

As we walked through the halls, the Sisyphean nature of the ongoing battle became clear. Power is still held by the landowners – plantations handed down generation after generation.

Morry’s parents were members of the Johnson Administration – her father, Special Assistant to the President for Health Education and Welfare, and her mother, one of Lady Bird’s emissaries. Of all the Great Society programs and laws passed during the Johnson Administration, her family was most proud of the Voting Rights Act. LBJ welded his political power and acumen to force it through Congress. In his speech to Congress, he defied his fellow Southerners, and exhorted the nation that “We Shall Overcome.”

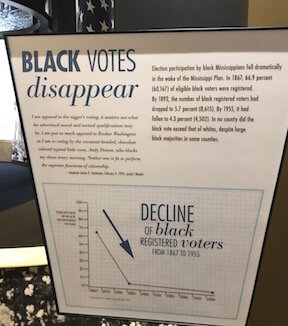

But the battle did not end with passage of this law. Local authorities continued to defy the federal government and refused to register blacks. Today, the effort to suppress minority vote continues through redrawn districts, voter id laws, reduced polling locations, and felon disenfranchisement, among other tactics.

Throughout the museum, a theme recurring: progress is not a straight line, two steps forward one step back, sometimes the reverse. Forging progress is hard, dangerous work. The leaders of the civil rights movement risked life, limb and their families for justice. Many lost all. The moral arc of the universe may bend, we hope, towards justice, but not without horrifying injustice along the way.

This truth ever present, as impeachment hearings start, and our President continues his dog whistling to mob like rallies across the South.

The sun was setting as we emerged from these dark halls of history, haunted by many questions: What makes it possible for any human being to inflict such horror on another? How could anyone endure this terror? What has happened since the sixties?

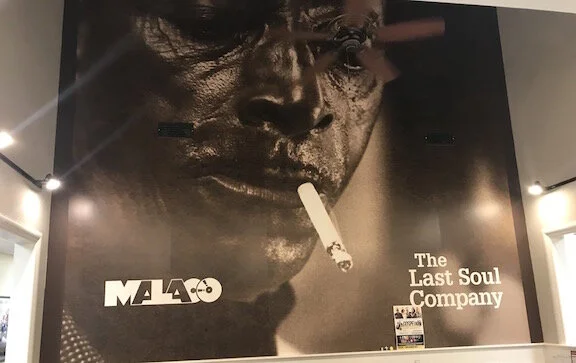

Sunday evening. Maleco Studios

Gospel and Blues was the only safe channel of expression then.

We spent the evening at Malaco Studios, which founders call “the last soul company.”

Owners Wolf Stevenson and Tommy Couch were students at Ole Miss in the early sixties booking bands for frat parties. After graduation, they opened a booking company, and enjoyed an initial burst of business with bands like Herman’s Hermits, The Who, the Animals and others.They then opened a recording studio, and began experimenting with local artists and songwriters, mostly gospel and blues.Their website says “making black music for black people.”Their halls are lined with Grammy awards and pictures of some of the greats like Mississippi Fred McDowell, Dorothy Moore and Lou Rawls.

And while he regaled us with stories of their rise, it felt oddly disconnected from the turmoil of the time. Certainly they were not immune as these black bands performed across the South -- separate sometimes no bathrooms, back doors, violence.

Asked about this later, Wolf wrote: “Considering the tragic riots on the Ole Miss campus in the fall of ’62, the relationships we had with the black bands and artists we booked from ’63 through ’66 when I graduated were very good, and they were accepted and appreciated by the frats & sororities where they entertained. I say all this not to deny that racial prejudice was present all around us, but to emphasize the burgeoning realization by many of our friends and associates that segregation and racial prejudices were perhaps not such a good idea after all…even though that’s just what we had long been led to believe, often by our families, was completely normal. I firmly believe that music, black music, was in many ways a step towards closing the racial divide of the time, even though ever so slowly.”

Monday Morning. Medgar Wiley Evers.

His modest ranch house, sitting on a neat nearly middle class street surrounded by a poor and disheveled neighborhood, remains the same as the day he was shot. The bullet holes, the furniture, the family pictures. The children’s mattresses still on the floor, as the Evers had placed, to stay below windows and line of shot. Some kind of mold is infiltrating from the roof – which Evers deliberately covered with rocks to help retard flames from fire bombings. Unlike other houses on the block, the Evers home had a front door tucked under the car park, another precaution designed by Evers. He taught his family to get out of the car on that side and walk directly into the house.

Tougaloo College has spent the intervening years trying to maintain this house museum through contributions and college resources. Finally, it has qualified as a national historic site, and will come under National Park Service purview.

Minnie Watson, museum curator, Tougaloo College archivist and our guide, is a lifelong Mississippi native, knew the Evers, and lived through the many battles for rights.

Insert: Minniebythefrig

She spoke about the fear that ran through Myrlie Evers’ every day. As a mother, as a wife, as an African American, she was angry a lot of the time. She supported Medgar and the NAACP of course – but she was desperate to keep her children safe, which they were not. The night Medgar was assassinated – her son had just been grabbing a snack from the frig – which still has the bullet’s dent in the door.

Evers was gunned down in his own driveway doing something he had trained his family never to do: walking exposed behind the car. He was retrieving t-shirts from his trunk for the next day’s rally: “JIM CROW MUST GO” emblazoned on the front. The day before, June 11, 1963, George Wallace had stood in the door of the University of Alabama, defying federal law as he attempted to prevent two black students from registering.

Insert: What was Jim Crow pix [caption: handout]

When the shot rang out – Myrlie and the children were watching JFK talk about the confrontation and successful registration on television. They quickly followed protocol: Crawl on the floor to the bathroom and shelter in the tub. The bullet tore off part of Evers’ torso, penetrated the house outer wall, then the inner wall between living room and kitchen, ricocheted off the refrigerator and came to rest on the opposite counter. It was the 1917 wartime assault weapon, the Ensign -- designed to destroy – that ultimately led an intrepid detective, unusual at the time for these kinds of crimes, to the assassin.

Evers lay, still alive, in the driveway. He died later that night in a hospital that initially refused to treat him because he was black.

His assassin was taken to court three times, acquitted twice. Finally on February 4, 1994, a Greenwood MI fertilizer salesman Byron de la Beckwith was convicted of murder.

Pix: Everssoldier

Medgar Evers was a gentle man, served his country in WWII, and was a leader in the non-violent approach to change. This despite witnessing the lynching of his father’s best friend. This despite the racial terrorism inflicted by Jim Crow laws, beatings and lynchings. This despite the continual violent assaults on him and his family because of his work to achieve equal rights. How? Where did his anger go?

The words of forgiveness uttered by the mother of a Charleston church shooting victim at Dylan Roof’s sentencing raises the same question. Example of greatness, even saintliness. Yet criticized within the African American community for being, yet again, subservient, willing to bow down and accept what the white man [and woman] does, [or does not do to end], oppression of a people.

Driving deep into Cotton Country

We left Jackson, driving deep into the Delta, on our way to Greenwood Mississippi. Cotton fields stretched to the horizon. [insert cotton pic]. Cotton was then what oil is today — a commodity that commands and controls regimes, even as it is used to command and control their people.

On our way, we listened to 1619, the NYT podcast. It traces the insidious impact of cotton on turbocharging the slave trade, spurring a global financing market, and roiling the US economy. After the cotton gin was invented, plantation owners could produce more cotton, and needed more slaves and more land. The federal government obliged by moving native Americans off their land and giving it to plantation owners. The banks obliged by allowing land owners to borrow more money using their slaves as collateral, which they bundled (much like subprime mortgage backed securities that preceded the Great Recession) and sold on the world market. When the price of cotton plummeted, so did the global economy.

Baptist town – Greenwood Mississippi.

Greenwood Mississippi – the home of Bryon de la Beckwith, the birthplace, according to some sources, of the first White Citizen Council, and the county where Emmett Till was murdered. Situated in the heart of the Mississippi Delta, at the confluence of two rivers, Yalobusha and Tallahatchie, which together form the Yazoo, Greenwood is the county seat of Leflore county, and was a major shipping point for the export of cotton to major markets, and the import of thousands of slaves, which totaled over a million in forced relocation to the deep south before the civil war. It is also the dominion that confines Baptist Town.

In the early 20th century, Baptist Town was one of the poorest black communities in America. It still is. The shotgun houses from sharecropping days still stand, and still house an entirely black community. Electricity and water are improvements. So is the fact that these residents can now cross the railroad tracks, and walk on main street any hour of the day. But other than that –the deep structures of plantation economy continue. For the most part, the same handful of plantation families who owned these black families continue to own the land. Sylvester Hoover, our guide for the afternoon, was born to sharecroppers who were born to slaves. They worked the same land, with hardly different conditions. Paid just enough to repay debt to the company store. Everyone worked the fields, picking cotton. “You couldn’t be too young or too old,” he recounted. “You had to be in the fields. You were not allowed on the streets.” See his description of being a child in the fields.

Before embarking on a tour, a young man stood just outside the Hoovers’ tiny, sparsely stocked convenient store, dollar in his hand. The only food establishment in what is otherwise a food desert. “We are not cooking today – come back later, “ Hoover brushed by him. Sylvester and his wife run a little grill inside the store – making burgers for locals.

The streets of Baptist Town were rutted, barely paved. Sidewalks overgrown and uneven at best. The cemeteries vacant lots, with tombstones overturned, overgrown, cracked or collapsed – like teeth smashed and scattered by a terrific blow.

A number of residents sat on their front stoops – despite the 40-degree weather. It was unclear whether they were home because it was Veterans Day, or they were unemployed. It was uncomfortable to consider what they might think of us. Oglers? could they trust we had respect, empathy? We waved, said hello and they responded kindly.

Standing in the dark of a sharecroppers shack, Sylvester exhorted us to try to imagine coming back to this dark, very cold (or very hot) coffin of a house after twelve grueling hours in the fields. This he said was birth place to the Blues. Robert Johnson played just outside, on the opposite corner. When asked if Johnson had also died on that corner, Hoover laughed “Naw - the guy who made the sign got his facts wrong.” Underscoring the malleable nature of history’s narratives, and importance of who controls the mic.

Montage: cemetarypix, shotgunhousepix, johnsonsign

We took a pilgrimage to three unmarked spots important to Johnson’s life and mysterious death. Greenwood is also the home to WGRM on Howard Street, which aired B.B. King’s first live broadcast in 1940. On Sunday nights, King performed live gospel music as part of a quartet. Until the late 1960s, King only played to black audiences.

We followed Stokely Carmichael and Martin Luther King’s travels through Baptist Town and Greenwood, It was here, in Broad Street park, that Carmichael first gave voice to Black Power. He had just emerged from jail for pitching tents for freedom marchers, who had flooded to Mississippi after James Meredith was shot by a sniper on his one man march from Memphis to Jackson.

“This is the twenty-seventh time I have been arrested—and I ain't going to jail no more! The only way we gonna stop them white men from whuppin' us is to take over. We been sayin' "freedom" for six years and we ain't got nothin'. What we gonna start saying now is Black Power!”

[insert Marylookingatmarker]

King was against using the slogan, and so began the division between elders and young black leaders over the movement’s fundamental philosophy. Whether to continue the non-violent ‘turn the other cheek’ approach of King and Gandhi, or to become more confrontational. Even as Carmichael, Malcolm X and others were framed in the media and by white opposition, as preaching violence – none of these leaders ever advocated violence as a first resort. Instead, they exhorted its use only when violence had been done unto them first. The problem, however, is that violence against blacks was the norm.

Sylvester took us to the slave turned servant cabin on a nearby plantation – the woman who lived and died in that cabin, cared for the owner’s children. She also was the last one to see Robert Johnson alive – according to Hoover.

[insert pix of slavecabin]

He took us to the oldest black church in the county – built in 1871 – where he learned to read. The closest black public school was six miles away, too far to walk, and severely underfunded. During the week, the church was used by the Rosenwald schools, more than 5,000 of which were established to educate African American children in the south during the early twentieth century, a partnership between Julius Rosenwald, a Jewish-American clothier who was part owner and president of Sears, Roebuck and Company, and Booker T. Washington, president of Tuskegee Institute.

The church is also where Robert Johnson is buried, according to local lore.

Montage: momarysylvestor, hooverchurch, johnsongravestone

Sylvester drove us miles and miles, peppering the ride with stories that seemed to grow as we drove. His tourism company, his convenience store in Baptist Town, his gigs as movie location expert, and his wife’s own role in The Help – helping to fund a middle class life, outside Baptist Town. His children all college educated, and professionals. He is friends with the white proprietors in town. He has bought a block of main street real estate – still not sure what to do with it. Yes times have changed. But still.

Greenwood is poor. Not the booming town of the early 20th century, when the U.S. Chamber of Commerce named Grand Boulevard one of the ten most beautiful in the country. Its population has been shrinking for decades, partly due to mechanization of cotton cultivation and the loss of sharecropping jobs, partly due to the reign of terror and migration north of African Americans, and partly due to white flight to more segregated nearby towns. It is now 67% African American, and in 2006, Greenwood elected its first female and first African American mayor – but as Minnie Howard attested, that often means state dollars are diverted to towns still in white control. “Cotton Row” on the banks of the Yazoo River - where slaves came in and cotton went out - now houses quaint shops and restaurants, and is the site of the Juneteenth jazz festival, not sure how often it is held.

We ate at the only lunch place open on Veterans day – Fox television playing, good old greens, stewed vegetables and fried chicken. On the television, a recurring advertisement: Attention farmers if you have used Roundup you are at risk for Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma. And this state stands solidly behind Trumps EPA rollbacks.

It was a wild day – with the weather underscoring our experience. Huge, dark ominous clouds rolled in, whipping up winds, and dumping flash flood-like torrential rains. This is when we embarked on the last journey of Emmett Till, the fourteen year old African-American visiting cousins for the summer from Chicago who was abducted tortured and murdered in 1955. His mother decided to have an open casket to show the world what had happened to her son, and catalyzed the civil rights movement.

[insert emmetttillmurder pix]

We stopped in Money, MI to view the overgrown wreck of a building that was the Bryants store. This was a white owned store that catered to black sharecroppers, and where Emmett Till was accused of grabbing the storeowner’s wife and whispering derogatory words. After they were acquitted, and protected by double jeopardy, Roy and his half brother J.W. Milam sold their confession to Look magazine for $4000. In 2017, a newly published book included an interview with Carolyn Bryant where she acknowledged she had fabricated the interaction with Till. The historic gas station next door is bright and newly renovated for visitors. The store on the other hand is condemned. Sylvester explained this was part of the ongoing suppression of Till’s story by the state. He then said that the current Governor was the nephew of Roy and Carolyn Bryant. The Governor has not refuted this claim, and his Wiki page confirms it.

We drove the long, dark road to the Sumner Courthouse, a scene that captured national media attention in 1955. No hotels allowed black reporters, who had to sit in a segregated section of the courthouse. Sheriff Strider welcomed black spectators coming back from lunch with "Hello, Niggers!" Jury members were allowed to drink beer on duty, and many white male spectators wore handguns.

Across the street from the Courthouse sits the Emmett Till Interpretive Center, a mostly bare large office space with one desk, and a room lined with panels that trace the murder and trail. It had been left open for Sylvester by the executive director, a young white lawyer who Sylvester says is a friend, and not popular in the white community because of his work.

One can only imagine the stakes for Moses Wright, Emmett Till’s uncle, who had opened the door to the murderers. Faced with death threats, he nonetheless took the stand to identify the two men. On September 23 the all-white, all-male jury (both women and blacks had been banned) acquitted both defendants after a 67-minute deliberation; one juror said, "If we hadn't stopped to drink pop, it wouldn't have taken that long." Moses and two other witnesses were forced to leave the state for their own safety shortly after the trial.

Montage: mosesidentifieskillers, interpretivecenter

We then headed for the sites where Till was killed, and thrown in the river with a cotton gin tied to his neck. The thunderstorm intensified, sheets of water hit the windshield, the wipers were unable to keep up. We turned off the paved road, and came to a stop in front of the barn where Till was tortured, we then turned down a dirt road towards the river to find the Emmett Till historical marker. This is the third such marker, the other two shot up with bullet holes, and it was bullet proof this time. Just three weeks earlier, shortly after it was newly installed, the KKK held a rally around it. As we drove, it seemed to get darker. At one point Sylvester said “This sure is creepy – I’m a little scared. I hope those guys aren’t around.”

Imagine. 2019. This proud strong African American with real reason to be frightened.

We got to Graball Landing, the sight where they pulled Till’s body from the river. The driving rain was freezing. Having come so long, we had to get a photograph – which of course is hardly more than a blur.

[insert graballlanding pix]

On the way to Little Rock Arkansas

We crossed the Mississippi river into Arkansas late Monday night. The difference was palpable. From the roads to the streetlights, neighborhoods to commerce centers – Arkansas seemed more vibrant, more diverse than Mississippi.

Perhaps better race relations has something to do with it? Despite having had a cotton-based economy, Arkansas is now the headquarters for six Fortune 500 companies. Multinationals are not going to places with deeply embedded racist policies.

Central High, Little Rock, Arkansas

Little Rock had big ambition. In the early 1950s, it was locked neck in neck with Atlanta in a race to become the metropolis of the South. That is why it invested over a million dollars in a state of the art school – Central High. [insert centralhigh pix]. That would be over $10 million today.

After decades of Supreme Court decisions upholding segregation, (Dred Scott, Civil Rights 1883, Plessy v Ferguson), they finally handed down a decision in 1954 that changed the trajectory of history. Brown v Board of Education, which simply put said it was not okay to have “separate but equal” schools – not just because it was obvious they were not equal though it was. No, the decision relied in part on evidence of the psychological impact that separation had on children. The research, based partly on what became know as the “doll test” showed that segregated schools created a sense of inferiority and self-hatred in black children.

Montage: classroom pix; dolltest pix

The Little Rock Nine wanted to go to the best school in Arkansas. They were bright ambitious young women and men who, along with their parents, recognized the critical importance, and opportunity of integrating Central High. The national media did too.

Governor Faubus went on television the night before the students were to enter to warn of violence, and ordered the National Guard to stand guard, preserve the peace, and prevent the students from entering. This served as a dog whistle to every segregationist – who showed up and created the violence.

The National Parks young guide did a terrific job of conveying how dangerous it was. The mob had a life of its own, growing in numbers anger and violence over the three days it took to get the students admitted. They broke into the school at one point to find the students, reportedly telling the National Guard “Just give us one of those N----- we can lynch and we will leave you alone.”

The national media, it turns out, not only protected these children by focusing world attention on their cause, but by becoming the physical buffer between the kids and the mob. One black reporter died of a head wound inflicted by the crowd.

Montage: centralhighhatrid,chhatred2,hatredcentralhigh

The heroism of the Little Rock Nine cannot be understated. So too little Ruby Bridges, who on Nov 14th 59 years earlier, at 6 years old, withstood similar hatred, if not the same level of violence.

[insert Ruby Bridges photo]

The story little told is what happened after the 101st Airborne (deployed by Eisenhower without its black members) left Central High. The students were subjected rage and hostility every day, ranging from name calling to target practice. They were hit with spit, trash, combo locks, burning paper and acid. The Arkansas National Guard, which had been federalized by Eisenhower (who was not a fan of integration but rose to what many called his ‘finest hour’) had split loyalties, and as one said directly to the students “We are here to make sure you don’t die, not to keep you from being hurt.”

After a year, Governor Faubus prevailed in shutting down all Little Rock Schools rather than continue with integration. Whites began their long exodus to “seg” academies, and black students were left with no where to go to school for a year, and then increasingly poorer and poorer schools in the years that followed. Many of the Little Rock Nine left the state. A Time magazine survey found Faubus was the fourth most popular leader in America.

The iconic photo of Elizabeth Eckford walking through the mob, head down, with a young white woman, face contorted in hate, screaming from behind, went viral globally, despite the dial up conditions of communications. Forty years after the fact, Elizabeth and the white woman came together, in what the National Park Service guide described as a beautiful reconciliation. The white woman, Hazel Bryant, apologized to Elizabeth, and said she hated that she has gone down in history as such a symbol of hate. And while they were reported to be “friends”, it didn’t last long. Elizabeth, who suffered depression and attempted suicide in the years following the Central High trauma, was eventually diagnosed with PTSD. And try as she might to let bygones be bygones, the wound was, is, too raw.

Indeed, one of the Little Rock nine benches that form a semi-circle in front of Central High, had been defaced with a slur.

That is what we learned. The wound is still fresh because the racial inequities are still vast.

Education was a primary, if less well reported, focus of the NAACP. Their battles for equal funding for faculty and facilities were met by the rise of White Citizen Councils and the passage of policies that embedded inequities across the South. But the fundamental divide begins with education, which remains as segregated and challenging today as it was in 1954. After aggressive measures to integrate schools, America is re-segregating. Harper’s magazine ran a cover story in 2014 “Still Separate, Still Unequal.” And the achievement and economic gap continue to widen.

Perhaps the enduring legacy of the Little Rock Nine is the inspiration they have given to many that followed. The National Parks documentary is powerful and moving – featuring teenagers across the country mobilizing to protect the rights of LGBTQ and Native Americans. It was no small satisfaction to us that they featured a group fighting to pass climate change laws. None of these kids face the level of violence the Nine suffered, and all were working in an entirely different media environment – crowd sourced and noisier, but greater opportunity to change the narrative.

That night, we stayed in the suburbs. The staff and clientele fully integrated. We could have been anywhere.

On to Memphis

The day started below freezing, so we made our way to what comes naturally in Arkansas – WalMart – for long underwear.

The drive to Memphis is one long flat field, dotted with cotton fields and trees in various stages of foliage.

We were pointed to the Lorraine Motel – now Museum. The route, therefore, into Memphis was perhaps not its premiere – but suggested a town like the other southern towns we visited – trapped in time. The predominated architecture was mid to late sixties.

The Lorraine Museum is upsetting, disturbing, compelling, inspiring and heart breaking.

Montage: lorrainebalcony, statesdenyvote, lowdescountry, oldladyvote, blacksfirstvote, threecivilrightsworkers

After you stand beneath the balcony where Dr. King was assassinated, after you pass through the room where he spent his last day, after you trace the progress of his life and the civil rights movement he helped create and lead, down the walls of this museum – the sights and sounds of the struggle surrounding, encapsulating, taking you back in time – after all that, perhaps most overwhelming of the experience is the power of his voice. Booming, deep, resonant, hallowed. Sublime. As if it came through him, not of him. His last speech a rousing call to action delivered to a packed audience on a stormy night. Playing in a chapel like room at the exhibit’s end, he divines his own death with holy inspiration, the night before he was killed.

We think if saints exist, he is surely one.

His voice. Where did it go? How has it receded so far into the distance? What has happened to the many voices since?

Beale Street

Even on a frigid Wednesday night Beale Street was happening. The birthplace of Memphis Blues, delivering some of the world’s greatest artists from the depths of the Delta, this is the namesake of Riley King aka “Beale Street Blues Boy” and finally “B.B. King.”

Jonathan Ellison, the latest successor to the crown King of Beale Street, and his P.S. Band played for us at B.B. King’s Blues Club. [insert BEALESSTREET mov}

All patrons, save two, were white. And those who danced probably shouldn’t have. It was hard not to move, though – the beat struck deep in the marrow of your bones. And, spoke to the truth to Wolf’s belief that music connects us, across ideology, history, hurt.

[insert this video:

And Now for Something Completely Different

Graceland, Graceland, Memphis Tennessee. We’re going to Graceland

Huge. That’s the only word that applies. Huge gate. Huge entryway. Huge Hallways. Huge and numerous gift shops. Clearly to accommodate Elvis adoring hordes, though Thursday morning was relatively quiet.

Treated to a VIP tour, we saw Elvis up close and personal. And he wasn’t what we thought. Of course the whole point of the place is to hold up a shining image of his life and times, so there was no talk of drugs, divorce or demise.

But still. The man was sweet, earnest, honest and very generous. Coming from poor and very humble roots – he never lost the genuine appreciation for how far he’d come, and everyone who made it possible.

He burst onto the music scene in a way only the South could deliver. At 16 years old, he went to record a birthday song for his beloved mother at a local recording studio. Not long after, the studio head said within earshot of his secretary “If I had a white man who could sing like a black man, I’d make a million dollars.” She knew just the guy, and the rest is history.

Fun fact – Elvis owned a solar powered car!

Montage:

welcometograceland, poorfamily, elvis, maryev, gracemasion

Somerville, Fayette County

We drove east out of Memphis, back to the summer of 1964. As Fayette is a relatively close suburb of Memphis, we anticipated malls and subdivisions – but surprisingly, or not , there were none. The landscape had barely changed since Mary’s summer in Somerville. We were curious if the same was true of the politics.

Town center could have been a postcard from that earlier town – the courthouse, the stores –it was all as Mary remembered.

[insert Mary pix of courthouse- she has]

We stumbled on a new restaurant tucked on a side street – with barely any signage – for lunch. Fayette County’s Judge was in the midst of his when we sat down. Two obvious out-of-towners cannot go incognito in a little place like Somerville, and soon Mary was introducing ourselves to the Judge, and her role in voter registration years before. The conversation could have gone either way. Turns out the Judge was relatively new (hard fought) and relatively liberal. He was quick to thank Mary for her work, and talk about the barriers that remain. Here too the same six or seven families who owned all the land, still do, and control most of the politics.

We drove in search of the house of Mary’s fearless leader – xxxx – and we think we found the place, same but older, and more dilapidated.

Ole Miss

Our route to Birmingham went through Oxford Mississippi – the home to Ole Miss and the site of violent riots in 1962, when the first African American James Meredith tried to enroll. It was one of the deadliest of school desegregation moments – two people were killed, thousands injured. Meredith graduated at the end of that school year, still guarded 24/7 by hundreds of troops.

Bombingham Birmingham

The most segregated city in America. The “Big Mules” – the city’s industrial magnates – segregated the workplace, and lobbied to do so throughout society. Morry’s great grandfather was a Big Mule, something she did not know until researching recently.

Dogs, hoses, burning crosses, firebombs. Across the South, sit-ins, marches, attempts to enroll, attempts to vote were met with violence.

Martin Luther King, Rev James Bevel, Ella Baker, Stokely Carmichael and the many leaders of SCLC, NAACP and SNCC sought to create “crisis that fosters such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue,” as King wrote from Birmingham Jail.

The Children’s Crusade was perhaps the most desperate attempt to stop the madness. How could Alabama treat children with the same hatred and brutality. King’s arrest had faded into media memory – the campaign needed something. Bevel suggested letting the children march and fill up the jails. There was much dissent. But on May 2, 1963 hundreds of school children met at 16th Street Baptist Church before marching downtown. They didn’t get beyond the park across the street before Bull Connor [insert bullconnor pix] and his firemen turned high-powered hoses on them. They kept marching. By May 6 2500 had been arrested.

On May 8 city leaders and SCLC agreed to integrate public facilities including schools within 90 days. The first schools would be Sept 4.

On early morning of September 15th, five children were changing into their choir robes when the bomb went off, crushing four, blinding the fifth, and blowing the face out of Jesus.

[insert missingface]

montage: childrensmarch, woundedgirl, fivekids,

They now have a black Jesus.

insert: black jesus

Across the street, where inner city row houses used to be, stands a proud museum.

Its chronicles were much like those we followed in Jackson, Little Rock, and Memphis museums, but with an Alabama lens. And like the sometimes random, often accidental, and many times deliberate accounting of history, certain themes became more self evident to us as we walked through its halls.

Here, we confronted the constant, systematic and insidious means through which American white culture, its vicious memes and caricatures, through airwaves, across news pages, in shop windows and school books, branded and imprisoned the African American. Shiftless, lazy, stupid, immoral. Molding the public image, and shaping the very private beliefs, from the moment you are born. Getting inside your mind, burying a voice do deep it sounds like your own, constantly, firmly saying – you have no value.

Montage: Coonjemima, lifesavers, waterfountains, cannotplayord

You cannot achieve what you cannot dream.

Well worth the time: A gobsmacking CBS news story about the “Reign of Terror” in Birmingham, and local reaction

Make Me An Angel That Flies From Montgomery – the Slave Trade Capital

Traveling to Montgomery, we rode along the rail lines that had been built by slaves to import slaves from the north to the south, in our country’s largest migration – an estimated million slaves ripped from their homes and families and brought to the South. The boom in domestic slave trading an unintended consequence of the ban on international slave trading.

Morry’s other great grandfather, Frank Yarborough Anderson, was instrumental in the Alabama Great Southern Railway, which built the New Orleans & North Eastern railway. His father William O. Winston ran Will’s Valley Railroad Company, which built the tracks between Birmingham and Chattanooga. Was the slave trade their driving economic force? Winston served in the Alabama House of Representatives, and voted against secession, though once the vote was cast he sent for his son at West Point to join the southern forces. Since her parents left Alabama and never looked back, she was completely unaware. Until now.

The Rosa Parks museum provides yet another wonderful slant on the history we tracked all week. Her Story. Here we heard about the women who drove an entirely grassroots and spontaneous boycott. Not the orchestrated male dominated campaign other museums suggested. There were hundreds of heroes whose names we know, and those whose names are little known or remembered, many of them women. From Fannie Lou Hammer to Diane Nash, Ruby Doris Robinson to Ida B Wells, Janie Forsyth to Septima Poinsette Clark. Many others who never made it into print, who died without a sound.

The integrity of the civil rights movement is clear at every turn. Here, the bus boycott’s manifesto mirrors the Declaration of Independence, laying out in specific detail the grievances that left no other recourse than to boycott. [insert Decdoc]

All this leading us to the Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Museum and Memorial to Peace and Justice.

Descending a dark ramp into the bowels of this cobblestoned warehouse, where little over a century ago slaves were chained and stored for auction down the block, we arrive at a series of cells. Inside each one, a ghostly hologram tells its slave’s story in painful detail. Two little children wrenched from their mother. A father who cannot find his family. Other worldly. It unmoors you.

From there you follow the slave’s path, out of the plantation and into prison. State convict leasing became big business after the civil war. Jim Crow laws swept the street each day, collecting the men of that generation and conscripting them to labor, often on the very plantations they used to live. Their very discounted wages were paid to the State. Fast forward one hundred years, and the structural inequities of today’s criminal justice system don’t look that different from Jim Crow’s. At each stage of the path, terrorism was used to enforce the caste system.

EJI is hard at work inside prisons, representing the wrongly accused and trying to mitigate the overly harsh sentences. For every victory, there are hundreds of black Americans still trapped behind bars.

Morry has spent time inside San Quentin where she has met some of the brightest, most thoughtful, kind, articulate and so very wise young men she has ever encountered. Their current fate the result of tiny little twists along the way, the same twists that go unnoticed in a white male’s life.

And then, once out, many continue to be disenfranchised. When getting out the vote in Tennessee, Morry came upon a living room full of ex-felons who were more educated and engaged about the elections than anyone else she had met. And still they cannot vote.

From his jail cell, Martin Luther King wrote it is the white moderate, more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice, not the Klansman, who is the greatest obstacle to freedom for African Americans.

The Memorial [insert broadview]

Words cannot convey the power of this place.

[insert memfirstpix]

You start face to face with the huge heavy tombs etched with the names of lynching victims.

[facetofacetomb]

As you walk through county after county, the ground beneath you begins to drop, slowly, imperceptibly.

[lifting tombs]

Until you realize that the tombs are being hoisted above you

[insert: hangingtombswith names]

Step by step, they are lifted high. You can almost see them swinging.

[insert overhead]

Final pix: lynch memorial

There was controversy around this memorial. Why bring up ancient history. Montgomery wants to move on.

You cannot heal a wound until you debride it.

[insert : hopefortortured]

Despite it all, this memorial still evokes faith in the moral arc of the universe. Its very name: The National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

In the face of this legacy of hatred, violence, racial terrorism, this is a memorial that acknowledges damage to everyone involved -- even those who partook, witnessed, acculturated their children. Forgiveness. It takes your breath away.

What to do

The election of Barack Obama – the victory of hope over experience, the exoneration of America, the watershed moment dividing us from our evil past – was like a bandage, binding the open wound. A bandage since ripped off, reopening, re-infecting the lesion.

What do we do now?

In the last of his days, King was focused increasingly on poverty. The grinding, unending, inexorable erosion of opportunity, dignity, spirit. How could African Americans escape it when they are bound and shackled at birth? Their schools, their neighborhoods, their choices, their chances.

That is where to start.

The power of the purse is undeniable. It was the force that integrated buses, schools and hospitals. How can it be leveraged now -- when the poor have increasingly little purchase power, the federal government no intent.

The power of the vote also undeniable.

When reporting on the civil rights movement fifteen years later, Morry interviewed the notorious Selma Mayor who was in office during the Selma-Montgomery march and had stood defiant on the courthouse steps looking away from the caskets of his black citizen victims of racial terrorism. In a nationally broadcast interview he had called Dr. King “Martin Luther Coon” which he later said was a slip of the tongue. When Morry was with him, he sat with cattleprods and other tools of oppression on display behind his desk. Just before we started recording, he popped his gum out of his mouth and put it behind his ear. He reveled in stunning Northerners, and fulfilling their Southern stereotype. He explained he was really a moderate, but had to reflect the voting populace at the time. Once the Voting Rights Act was passed, he said, he had to change his ways a lot in order to stay elected. Morry also interviewed Eunita Blackwell of Mayersville Mississippi. Ms. Blackwell described the long lines of African Americans trying to register to vote, and the pickup trucks filled with angry white men and shotguns. When asked what the difference was between then and now - she replied “The difference is now I am the mayor!” She was the first African American woman elected mayor in Mississippi.

The power of the vote is still fundamental to our democracy, but vested interests have only gotten more powerful in their ongoing perversion of democracy’s very mechanisms. The vote is trusted less, exercised less. A self fulfilling prophesy.

And America’s watchdogs – the media –-- the only reason our nation reckoned with injustice in the sixties – is in the midst of huge technological disruption, shrinking mainstream media, exploding opinion media and growing an internet designed to give you back only what you want to know. The result: our ideological bubbles more isolated and insulated than ever.

We think we have never seen worse. But clearly, if this trip has taught us anything, we have.

Martin Luther King had faith in the moral arc of the universe. He had a steadfast moral compass. And he had his spiritual guide.

[insert epiphany]

Perhaps today’s crisis is necessary for our next major advancement. Perhaps technology will deliver a better democracy, where crowdsourcing is king. Perhaps the egregious regression of the post Obama era will birth an even more noble virtuous populace.

Perhaps. But nothing is going to happen on its own.

We cannot, will not, be King’s moderate whites who lament the problem and look the other way.

It is up to us to bend the moral arc of the universe towards justice.

Postscript from Morry

As we drove through the South, my own family’s history became more clear, and my heart burn more painful. Sickening. Deeply. Inheritance didn’t pass to girls and my Dad’s family was dirt poor, so, for what it’s worth, my parents were free of direct blood money. But still, they and I benefited from decades of white privilege and oppression.

I remember my mother telling me stories of her youth -- seeing a very beautiful black woman when she was a child and being reprimanded by her mother that “we don’t use the word beautiful to describe Negros.” And then coming to DC, and her first bus ride sitting next to an African American man. “I was unable to move, frozen. Strange.” I couldn’t understand. That seemed like ancient history. So very different from the home they created.

They had fled the South, and worked to build the Great Society in the Johnson Administration. They were crusaders. They My dad wrote the legislation that provided federal funding for primary and second schools – essential to desegregation, and to evening the uneven school funding ledgers. Their friends many prominent leaders in civil rights — Virginia Durr, James Maguire, and others. And while my parents’ social circle was mostly white – mine was decidedly different. I went public schools and my best friend was black, which sounds cliché but it wasn’t. When the riots broke out after Dr. King was killed, my sister and I went door-to-door raising money to help rebuild the inner city. My mother was Obama’s biggest fan. Still is. My dad would have been too, had he lived long enough. We campaigned for Obama. And yes this sounds pathetically self-serving.

I know my parents could have done more then. I could have done more too. But at least they broke the DNA chain of racism. And we aren’t dead yet. There is much left to do.